| ||

| ||

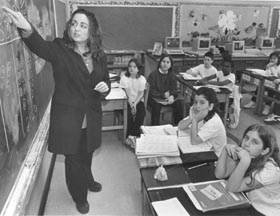

Aspiring teacher Terry Panetta PHOTO: CLAUDIO CALLIGARIS |

Trial by fire

|

BRONWYN CHESTER | Having a student teacher in the classroom was always a great opportunity for fooling around in grade school; the spitballs would fly, the insolence would increase and urgent needs to go to the bathroom would surge out of the blue -- at least for the first few days until the teacher-in-training had proven she or he was in control.

Looking back, it must have been hell for some of those young teachers. But survive, most of them did. At the Faculty of Education, for instance, the drop-out rate is less than four per cent, one of the lowest in the province. Professor Spencer Boudreau, director of the Office of Student Teaching, attributes this to the fact that it's highly competitive to get into McGill's program in the first place. And that the 10-day observation period in elementary and high schools, which McGill education students undertake in their first year, allows them to know what they're getting themselves into before they take a deeper plunge. In their third year, students get their first real taste of the classroom, taking on 75 per cent of the teaching load over a seven-week period. There is plenty of support, both from the "CT," or cooperating teacher, and from their McGill supervisor. Terry Panetta, who has just finished her third year, appreciated both. Her CT, Susan Wener, was "very helpful. "She would provide me with the class schedule one week in advance which really helped me plan my lessons," says Panetta, 22, adding that once a week she and the 26 other student teachers in the West Island area would meet with their professional supervisor Elaine Brooks to discuss their trials and tribulations. Brooks, a faculty lecturer who also gives the third year professional seminar, begins in January to prepare 300 third-year students for their foray into the classroom every February. The seminar deals with such matters as "classroom management," also known as discipline, which, she says, is "one of the students' greatest fears." Panetta, who taught a grade three and four class -- a half-day each -- in West Park Elementary, a French immersion school in Dollard des Ormeaux, had one experience of the dreaded "losing control." It was during her third week and the grade three class was testing her limits. "The next day, I sat them down and I wrote up the rules on the blackboard: 'I respect you and you will respect me. You must raise your hand if you wish to speak.' Then I kept them in at recess," said Panetta. Watching Panetta teach the grade four children some four weeks later, she seems like an old hand. The children clearly enjoy her way of teaching math and language arts and eagerly participate. Today, on the few occasions when the class has not been attentive, she counts to five. "I'm counting to five again… "Anyone else missing spelling books? "Lesson 21: Did anybody study?" Silence. "Duke, it sounds like duck," says Panetta, beginning the spelling quiz. This is her second-to-last day and many of the kids don't want her to go. "I'll miss her. I don't know if I'll ever have as good a teacher again," says 10-year-old Tanner Lippiat. "If she gives you hard stuff, she can explain it to make it more simple," says nine-year-old Amanda Katz. "She makes it fun for everyone; she doesn't leave anyone out," says Matthew Morgenstein, age nine. Every child has something nice to say. Panetta finds that putting herself in the place of the students helps in trying to relate material to their lives. "I've also learned to pace myself; everything takes longer than you think." But what's been central, she believes, to her success in the classroom is her feelings for the children. "I always knew I would work with children. I love children. That has to be first and foremost." Patricia Morrissette too has that love for her students, but hers are of the bigger variety. Training to be a high school English and history teacher, Morrissette did her third-year practicum at Centennial Regional High School in Greenfield Park, with a population of 1,650, the largest English-language high school in the province. Initially, she found the experience "very, very scary. "You're afraid you won't be able to do what you have to do. But it went better than I thought it would," she says in retrospect. "Thanks to Stephanie Vucko [the CT] who prepared the class for me and gave me the chance to observe the class for a few days, to see the various personalities." Like Panetta, Morrissette, also 22, experienced being tested, though the risks with bigger kids are usually greater. On one occasion, a boy came into class fuming and on the verge of tears. Sensing things could get violent and, at the same time, wanting to protect him from ridicule, she asked him if he'd like to talk with her outside the class. He'd had a fight that morning with his brother, then missed his bus and fallen into the mud in front of everyone. It was one of those mornings and Morrissette could empathize. She suggested he have a drink of water and collect himself before returning to class. Having access to a sympathetic ear helped him settle down. While Morrissette enjoyed the experience of working in a school with children from various cultures and social classes, part of her learning too had to do with pacing. Children with behavioural problems, for instance, "take up lots of time." For that reason, she appreciated learning the "Guided Independent Learning" Ð GIL Ð method used by Vucko whereby every Friday, the children are informed of their assignments for the week and it's up to them to plan how and when they are going to complete them. "It helps the students with reading, learning to budget their time and to be responsible for their learning," says Morrissette. She also learned about using technology both to help her students work independently and to develop their writing skills. Having both a written and electronic portfolio of writing to produce for the year's end, the students had to learn both the process of writing several drafts and of writing in various genres. Strongly influenced by Vucko's student-centred -- as opposed to curriculum-centred -- approach, Morrissette frequently had the students working in groups, criticizing (albeit anonymously) each other's work. "One of the most rewarding things is seeing children help each other out," she says. Morrissette's temporary charges also expressed regret when it was time for her to leave. "I'll miss her because she's nice and she does art with us," said Namissa Maguiraga, 13. Maguiraga also appreciated Morrissette for the fact that she is "young and understands us." Several children made a similar comment, appreciating Morrissette's youthfulness. They also commented on how student teachers, in general, make them feel important. "They're learning to be teachers so you can tell them stuff you know," noted Maguiraga. For 12-year-old Amanda Silas-O'Donnell, Morrissette was a source of inspiration. "It's fun, it's different because she's learning to be a teacher and that's what I want to do." Even if some of the students considered "Miss Morrissette" "very strict," they appreciated her authoritative way. "She's very different from other student teachers; she controls the class better," said 14-year-old Sara Ahmed. Teachers aren't obliged to take on the 1,000-plus student teachers McGill must place every year, but they do because it brings "new blood" into the classroom, says Susan Wener. Furthermore, it allows experienced teachers to share their knowledge, to be "mentors," says Vucko. And teachers often gain a new perspective on their pupils while the student is teaching. Wener also appreciates the fact that it allows her to spend more time with the students who really need extra help. In her experience, the benefits outweigh the risks. "The worst that could happen is that the student is not good and you might have to reteach things," she says. As for Morrissette and Panetta, life is much more relaxing now that they aren't juggling teaching, lesson preparation, marking, part-time jobs and school assignments. Panetta is working at a daycare this summer while Morrissette will be substitute teaching next month at Centennial High before doing a few summer courses. Next year is their last and by October they'll be back in the classroom for their final practicum. This time it's for eight weeks and 100 per cent of the teaching. Do they feel prepared? "I'll be nervous," says Morrissette, "but not like when I started this year. I can apply what I've learned to any setting."

|

|

| |||||