| ||

| ||

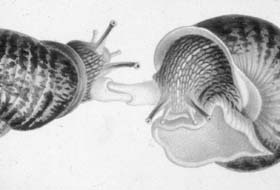

Helix aspera mutually inseminating each other DRAWING BY FÉRUSSAC, 1745-1815 |

Love hurts for snails

|

BRONWYN CHESTER | Birds do it, bees do it and snails do it -- but with a pointed difference. They do it with darts. Before mutual insemination -- snails are known in the business as "simultaneous reciprocal" hermaphrodites -- the amorous gastropods shoot centimetre-long darts out of their bodies and into the genital area of the other (which happens to be just behind the head on the right side).

Why, you ask? That's a question that malocologists (snail scholars), including McGill biology professor Ronald Chase, have been asking since at least the 17th century. Chase and biology doctoral student Joris Koene think they've come up with part of the answer, which they published in a recent issue of The Journal of Experimental Biology. According to Chase and Koene, it may be that the dart serves to transport a chemical contained in its mucus coating which causes contractions in the female reproductive organs, helping the sperm find its way into one of several tubules in the spermatheca sac, a sperm storage chamber. In other words, the dart acts as a sort of hypodermic needle, says Chase. When it comes to mating, snails could teach the bed-hopping denizens of Melrose Place a thing or two. They copulate frequently with many partners and can store sperm for up to two years. Only an estimated one-hundredth of one per cent, however, of donated sperm find their ultimate destination. So, "it would be advantageous for a sperm donor to increase the survival and utilization of his sperm relative to that of his competitors," write Koene and Chase. The idea being, of course, that every snail will do its utmost to ensure that his/her genes get expressed in a next generation. But success in reaching the spermatheca does not a father make. For, given the promiscuity of the gastropod, the sperm in the spermatheca will be from various donors. What, then, can a snail do to ensure posterity? Do better dart-shooters have a better chance at fatherhood? Chase and post-doctoral fellow Michael Landolfa are now working with the hypothesis that the more deeply embedded the dart, the greater the chance of a particular snail's sperm being "chosen" to fertilize his/her partner's eggs when the time is right. Snails dig themselves a burrow in the earth and lay their eggs only when there is sufficient humidity. In order to test their hypothesis, Landolfa will be genotyping the eventual baby snails and comparing them to their possible parent snails, all of whose dart-shooting skills have been observed and noted. There's a point -- no pun intended -- given, for instance, if the dart actually makes it into the partner; not all do. (In fact, Chase has a favourite slide of a snail with a centimetre-long white dart emerging from its head!) Some darts stay in only momentarily, while others may be deeply lodged; the depth of the latter will be measured. For the moment, Chase and Landolfa don't know if there's a prime target spot, but that's another factor they will observe over the coming months. If you're wondering about the mechanics of researching snails, these two-inch-long Californian imports are most obliging. Usually, Chase need only liberate the snails from their individual plastic "condos" in order for them to begin courtship. Twelve go into the "mating box" and when the activity gets serious, from one to four couples are moved to individual "nuptial suites," where they are observed. Chase and his snails have been together a long time, but never in their 27-year relationship has Helix aspersa brought him such attention as with the publication of the mucus-dart connection. ABCNEWS on the web, the British magazine Nature's on-line news service, Nature Australia magazine, Science Bizarre of the Discovery channel on-line magazine and, most recently, Quirks and Quarks, the CBC radio science show, have all paid attention. Chase, who's one of only a handful of people in the world studying the love dart, says he's "surprised by the attention. But I like it. "There seems to be lots of interest in snail sex around the world," he says with a chuckle.

|

|

| |||||