| ||

| ||

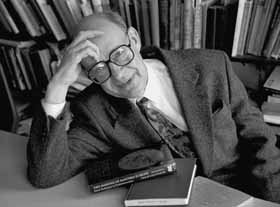

History professor Philip Longworth PHOTO: OWEN EGAN |

Hard road ahead for Eastern Europe

|

DANIEL McCABE | Thousands of Eastern Europeans must be thinking, "It wasn't supposed to be like this." In the heady days following the collapse of communism, a wave of optimism engulfed that part of the world -- the future would be undeniably bright.

It hasn't quite worked out that way. Poverty, crime, despair and violence -- especially in the former Yugoslavia -- are all part of the political and social fabric of contemporary Eastern Europe. Decades of stifling communist rule certainly contributed to the region's present-day problems, as have several serious miscues by post-communist leaders. But McGill history professor Philip Longworth, an expert on Eastern Europe, says the West hasn't been exactly blameless. The aid and assistance expected from Western countries to help the region overcome its economic difficulties have been disappointingly tepid. "When Gorbachev turned to former U.S. president George Bush, his response was, 'I'm sorry, I'm afraid our pocketbook is empty.'" And Longworth says there are other factors at play as well, some dating back centuries. To understand the Eastern Europe of 1998, you have to appreciate the often troubled history of the region. Longworth is the author of The Making of Eastern Europe, published in 1992, which earned glowing reviews from The Financial Times of London, Foreign Affairs and Choice magazine. He recently updated the work, adding a chapter on post-communism and the region's current plight. Longworth has strong views on the importance of history and laments in the introduction to his new edition that "most history taught in schools is confined to the recent past. "The more you know about the history of a place, the better you can understand why things are the way they are," says Longworth. He says his "warts and all" approach to history isn't always popular with nationalists who prefer a more "heroic" reading of their countries' past. "History can't foretell the future," says Longworth, "but it does close off certain options. A poor man isn't necessarily doomed to a life of poverty, but he certainly doesn't have the same choices as a rich man." And Eastern Europe has had a poor hand to play over the centuries. Throughout its history, the region has suffered repeated invasions -- by everyone from the Mongols to the Nazis. Perennial poverty has had a long-lasting "catch 22" effect on the countries in the region as well. As a result of poor living conditions, thousands of Eastern Europeans have emigrated to the West -- among them the best and brightest, the very individuals who could have contributed the most to building better economies had they stayed put. A powerful noble class held sway in Eastern Europe for a far longer period than was the case in Western Europe. The result -- major obstacles to the development of personal initiative. For a variety of reasons, cities were slow to evolve in the East as well. "You need the unique concentrations of talents and resources found in a city to build stable, durable institutions," says Longworth. The bitter nationalism that spurs suspicions and prejudices among different ethnic groups has also been a hindrance to Eastern Europe's development. Longworth also believes that East Europeans have been a little too easily swayed by utopianism for their own good. "There is a tendency to go for the strong stuff," he says. "Ideas become something of a drug and hopes tend to run unreasonably high." Surveying Eastern Europe's current state of affairs, Longworth says it's important to realize that the region has strengths as well. "They do have assets. There are oil and mineral resources. There is a highly educated population in many of these countries -- that's one of the good things that communism did." Longworth suspects that much of Eastern Europe will eventually join the European Union -- but that membership won't include all the benefits enjoyed by current members of the European Economic Community. "I think you'll see countries like Germany and France trying to protect their own interests and countries like Hungary and Poland will be offered a form of secondary memberships that don't include all the privileges of being in the EU. I fear that people in the East who think that this is going to be their meal ticket are going to be disappointed." Longworth's own interest in Eastern Europe was sparked when, as a young Cold War-era soldier, his facility for learning foreign languages drew the attention of his superiors. Scouted as a possible intelligence officer, Longworth was tutored in Russian. He never did become a spy, opting to become a different sort of intelligence officer -- a historian -- but his Russian lessons led him to develop a keen interest in Eastern Europe. He hopes his book will leave readers with "a more sympathetic view towards the region. I've been traveling back and forth since the 1960s and for all their problems, it really is a remarkably attractive part of the world."

|

|

| |||||