| ||

| ||

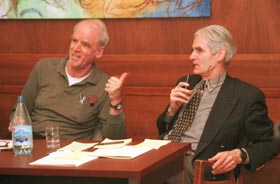

Charles Taylor and Gérard Bouchard PHOTO: OWEN EGAN |

Reexamining nationalism

|

SYLVAIN COMEAU | Nations and nationalism play a central role in today's world, even in an age of increasing globalism, speakers argued at a recent symposium.

Daniel Jacques, author of the recent book Nationalité et Modernité, said that nationalism has acquired an undeservedly bad reputation after a century of ethnically based conflicts. "Is nationalism still valuable, still the appropriate framework for confronting the challenges we face in the next century? It has long been the target of criticism. For many, the nation is too small to confront the challenges of globalization; for others, it is too large to deal with local concerns." The most common charge, which may have seemed outrageous earlier in the 20th century, is that nationalism has become an enemy of freedom. "Post war political philosophy is concerned with the problem of justice and the relation between liberty and equality… it often argues that the nation is contrary to freedom because it is contrary to world trends. "I would argue, instead, that the nation has allowed the realization of the freedoms we enjoy today." Jacques argued that a political realm which goes far beyond the boundaries of a nation -- such as that of globalization -- is antithetical to democracy. "If we accept the criticism of the nation, that leads us to the idea that there can be a form of democracy that can exist outside of nations. But what kind of freedom is still possible if we expand the political landscape to dimensions which go beyond the territory of the nation. That territory entails elements which are essential to participating in a democracy: a sense of belonging, a link to history, collective memory and a unique culture. These factors are missing in a global environment." McGill philosophy professor Charles Taylor, author of Multiculturalisme: différence et démocratie, agreed. But he raised troubling questions about the sometimes exclusionary nature of nationalist sentiment. "As soon as a people become a sovereign nation, problems emerge: who belongs, who doesn't belong, who feels tied to the nation, and who doesn't? If some groups don't feel a certain solidarity and identity, who don't feel like they're in the same boat as the principal group, democracy doesn't work." In extreme cases, that kind of exclusion has led to some of the worst excesses of ethnicity. Rather than threatening the integrity of a nation, inclusiveness may prevent violent and ultimately self destructive ethnic nationalism. "Some have demonized ethnicity, because in certain cases, such as in the former Yugoslavia, the creation of a people and a nation leads ultimately to ethnic cleansing. But these unfortunate cases do not amount to a condemnation of the ethnic dimensions of a nation. They condemn the autocratic regimes which exploit ethnic differences," said Taylor. "Ethnic nationalism is an unavoidable fact of life. But to remain viable, it can and must incorporate many identities."

|

|

| |||||