| ||

| ||

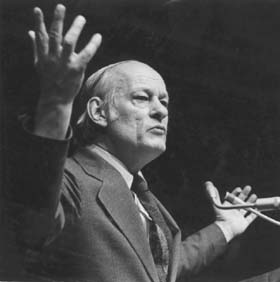

Former premier René Lévesque |

Reporting on the referendum: was there bias?

|

DANIEL McCABE | During the recent Quebec election, Premier Lucien Bouchard complained that the English press often portray him as a "devil," while rumours swirled that writers at La Presse were reprimanded by the newspaper's federalist owners for criticizing Prime Minister Jean Chrétien's performance during the campaign.

According to a new book by communications professor Gertrude Robinson, plus ça change when it comes to the unique tensions that surface when the Montreal press cover the politics of separatism. Language and different attitudes about Quebec sovereignty have long played a complicated role in determining how the province's various media cover the issue of independence, says Robinson, the principal author of Constructing the Quebec Referendum: French and English Voices in the Media. Preparing the book took years as a team of researchers examined reams of newspaper clippings and hundreds of hours of television coverage relating to the 1980 referendum on sovereignty-association. The research pointed to several factors that influenced the way the various media reported on the 1980 referendum. In one way, the English media had a far easier time of it -- the vast majority of English Montrealers were strongly opposed to the Oui side. "They clearly understood where their audience stood," says Robinson of the English press. The situation in French was far more complicated. Robinson says there were three categories of francophone voters: federalist, sovereignist and undecided. "The French press essentially had to address all these points of view at once, without alienating anyone," says Robinson. A tricky task, to be sure. As a result, the French press often backed away from analyzing major policy initiatives from either side, publishing big chunks of official documents, such as the PQ's White Paper on sovereignty-association, without commentary. Robinson says that such an approach has a decided disadvantage. "It makes for very boring reading. The English media was able to paraphrase what was in these documents without fear of offending their audience. They were able to use much more colourful language." According to the book, most broadcasters and newspapers adopted a similar approach to covering the referendum in one respect. Robinson writes that much of the coverage of the vote likened the referendum to a sports match -- a narrative technique common in journalism. The strategic wins and losses of each side were highlighted, while the more complex issues associated with the vote tended to get short shrift. "Lost in all of this were media discussions of the range of political options available to rebuild the Canadian federation and of different voter groups' more nuanced understanding of the issues of the day," she writes. Close to 80 per cent of francophone journalists voted for the Parti Québécois in the provincial election prior to the 1980 referendum, while 66 per cent declared themselves as supporters of sovereignty. Robinson posits that this may have put more pressure on these reporters to try to appear to be as balanced as possible in how they covered the referendum. Another factor was the largely federalist leaning of almost all the Montreal media owners. Not coincidentally, editorials were almost uniformly federalist. With the exception of Le Devoir, the editorial pages largely presented only one viewpoint -- the Non side. One veteran La Presse editorialist tried to write a pro-sovereignty editorial, but was turned down. At Le Devoir, however, editorialists were free to speak their mind: three wrote pro-Oui editorials, one composed a pro-Non essay. Robinson's collaborator, Armande Saint-Jean, who penned two of the book's chapters, describes the paper's ability to run editorials for both sides as a "remarkable and extremely rare case of support for editorial independence." The referendum occurred at an important juncture in Quebec's media history. Partisan publications such as the PQ's Le Jour had folded shortly before, resulting in the Quebec journalistic scene becoming patterned on the North American model (where major media are profit-driven businesses which aim to be seen as balanced and neutral in their reporting) as opposed to the European model (where many major newspapers are tied to a particular political point of view and often to political parties). Journalists who wanted to become politically active during the referendum discovered that their bosses weren't keen on the idea. Several were suspended. While media tried to seem balanced, Robinson says TV shows and newspapers adopted subtle strategies that bolstered one side of the debate over another. One Pulse News broadcast featured quotes from Liberal Party leader Claude Ryan and Premier René Lévesque on a contentious issue. Ryan was filmed during a relaxed, pre-arranged interview, Lévesque was caught offguard in a media scrum. While Ryan looked composed, Lévesque appeared dishevelled. The media also make choices about whom to interview, notes Robinson. The Gazette tended to turn mostly to Non supporters for quotes, while French television stations, in covering the PQ's White Paper, turned to PQ spokespersons for 61 per cent of their interviews. Robinson also examined the coverage of the most recent referendum, but not in the same painstakingly detailed way. It was enough to lead her to one important conclusion. "All those elements, all those differences are still in existence. They still influenced the way the 1995 referendum took place." Still, Robinson argues that Montrealers are "as well served by their media as anyone anywhere else in the country." She thinks most journalists do their best to cover stories as well as they can. Audiences just need to watch the news with a sceptical eye.

|

|

| |||||