| ||

| ||

|

|

DANIEL McCABE | Patrick Glenn is kicking himself for not learning Russian. Back in the early '90s, he was teaching a seminar on Russian law and decided he should know the language. Along came Perestroika and, overnight, much of the material in Glenn's seminar was out of date. "I thought to myself, 'Well, that was a badly picked area of specialty.'" So he quit his Russian language studies and moved on to teach other subjects.

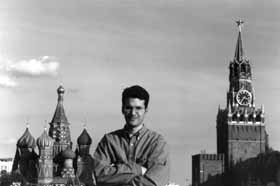

Today, Glenn is spearheading a project in which he and other McGill law professors are helping to shape the way law is made in Russia. And knowing the language would really come in handy. Russia is currently updating and reforming its civil code. The reformers are Russian justice department officials working in the country's Centre for Private Law, which reports directly to President Boris Yeltsin. The centre's efforts began in 1992 and the first two new codes were enacted two years later. "It was clear from the start that this was to be the motor for the liberalization of Russia's legal system and economy," says Glenn. As the centre started work on the next phase, McGill's Faculty of Law received two invitations to get involved in the process. The law firm Ogilvy Renault The faculty was also contacted by the Institute for Law Based Economy Backed by a $950,000 grant from the Canadian International Development Agency, McGill entered the game. Peter Sahlas, a McGill law student, was chosen to be McGill's man in Moscow and coordinator of the project. An international relations graduate from the University of Toronto who is fluent in Russian, Sahlas had already worked in St. Petersburg teaching English to Russian journalists. "He's done a remarkable job for us," says Glenn. That job required some quick thinking and quick action when the University's partner in the process, ILBE, became embroiled in controversy this summer. Press reports suggested that ILBE workers were breaking U.S. law by using their insider's knowledge of Russia to make improper investments. Harvard cut its ties to the group, which was also under attack from Russians uneasy with the notion of Americans having an influential role in Russian lawmaking. At a conference in Germany, Sahlas encountered the president of the Centre for Private Law. "In Moscow, he was a virtually inaccessible figure," explains Sahlas, who took the opportunity to make the case for McGill's continuing involvement. "We had a few animated discussions, and we agreed to meet back in Moscow after the conference. Our meetings and subsequent cooperation activities went very well." Meanwhile, sensing that trouble was at hand, Sahlas went into ILBE's office one night and removed McGill's computer and files. Soon after, the office was trashed and ILBE was out of the reform process. Thanks to Sahlas, McGill's materials were safe and sound and the University also had a direct line to the Centre for Private Law. "The professors at McGill are now part of the trusted inner circle of advisers to the President's civil law reform team," says Sahlas. Adds Glenn, "Before, we worked through ILBE and we were on the outside looking in." Sahlas says the Russian reformers deserve admiration. "The members of the drafting team work very long hours every week. Many of these experts could earn five times their salary if they accepted offers to work for foreign law firms in Moscow. Some of the leading judges in Russia also participate, despite the demands of their workload in court." He adds that the admiration is mutual. McGill's mastery of both civil and common law and its focus on comparative law helps give the Russians a sense of how different countries have approached similar legal questions. About 10 McGill law professors are involved in the project. They examine texts and drafts sent from the Russian centre and reply with comments and suggestions. The McGill participants are often under the gun to respond quickly. "There is real time pressure Glenn says there is no shortage of work to do. "If you look at the law of successions in Russia, for instance, well, there was no law of successions. There was no private property [under communist rule] so you didn't pass it on to anybody when you died. John Brierly and Madeleine Cantin-Cumyn have really affected what's being done in this area, they made some radical revisions." The project is paying dividends back at McGill as well. A research seminar devoted to the reforms and featuring presentations by some of the Russian lawmakers has had the largest student registration ever for a course of its kind. McGill's involvement in the project, which is also supported by Canada's Department of Foreign Affairs, has been both memorable and rewarding, says Glenn. "As academics, I think everybody involved would agree that it's been just fascinating to see up close the issues that they're dealing with. And I have absolutely no doubt that we're having an impact on the legislative process over there."

|

|

| |||||