Sister Prejean continues her fight

by Sylvain Comeau

Sister Helen Prejean is an unlikely celebrity, even in media-obsessed North America. But how many Catholic nuns have written number-one bestsellers and inspired Oscar winning performances?

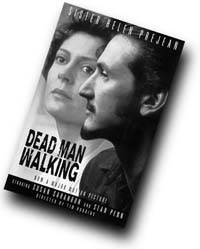

Prejean is the author of Dead Man Walking, about her experiences counselling death row inmates and victims' families. The book was adapted by director Tim Robbins in the film of the same name, which received four Academy Award nominations. Susan Sarandon took home the Oscar for her portrayal of Prejean, who spoke at the Palmer Amphitheatre on January 17.

"The one piece of advice I had been given about films was: 'Don't let anyone make a film of this story unless it's someone you absolutely trust.' When you sign away the rights to your work, they can do anything they want. They can make a musical comedy based on your stuff, and you have no control."

Prejean developed an instant rapport with Sarandon, who said she wanted to play the role of Prejean "because she was always looking for 'substantive characters to portray.'

"I met Susan, and I knew I could trust her. She talks about 'the vocation of acting.' She gets inside a person's skin, without judgement. That's the essence of compassion, too."

The project was a tough sell. "Tim shopped the script around to all the major studios, and they all turned it down. They all said, 'This could never be a box office success. You don't have a romantic interlude between the nun and the death row inmate; they don't even touch until the end. Plus, the guy is guilty as sin, he's not lovable, he's not sympathetic, and they're going to kill him in the end. It's a downer.'" Polygram Filmed Entertainment eventually took on the project.

The result was a critical success and Prejean, unlike many authors, was pleased with her book's transition to the screen. "The movie is not a polemic; it shows both sides of the issue. It raises deep questions, and it makes people think."

Although she discussed the making of the movie in depth, Prejean is more interested in the cause which inspired her book. She has become an outspoken critic of capital punishment, particularly the inconsistent--even prejudicial--way the sentence is imposed in the United States.

"When you get involved with something and you're watching people suffer, and you see the palpable injustice of a situation, a passion is born. And you have to speak up, especially when people don't have a voice."

Prejean admitted that she feels somewhat isolated in her cause.

"Who knows what's happening with the death penalty in the United States? Who's talking about it? Only politicians, when they run for office. Supporting the death penalty means a politician is 'tough on crime,' and anyone who doesn't is 'soft on crime.' They won't say that out of 23,000 homicides in the U.S. every year, less than one per cent of those found guilty will be chosen to pay the ultimate penalty."

Prejean charges that race and class are the two most important factors when that choice is made.

"From square one, it depends on who got killed. Young Virginia Smith was a 14-year-old girl who got dragged into the woods by three young men, who assaulted, raped and knifed her, and left her to bleed to death. That sure sounds like a matter for the death penalty, doesn't it?

"Yet, none of them got the death penalty; two of them didn't even get life sentences. Of course, Virginia Smith was a black girl in Louisiana, and those who killed and raped her were young white men, and their fathers all knew the district attorney. So race and (financial) resources come into play right away."

Prejean is aware that convicted murderers are seen by many as deserving of death, but she feels that this is because they have been dehumanized in people's eyes. When she was counselling Patrick Sonnier, the death row inmate portrayed in Dead Man Walking by Sean Penn, she was aware of his crimes but never forgot his humanity.

"The first sound I heard associated with him was the sound of chains dragging across the floor, and that was also one of the last sounds I would remember, as I walked behind him into the execution chamber.

"But I didn't know, the first time I went to see him, if he was going to be executed. All I knew was that I was peering through a heavy mesh screen into the face of a human being who was very glad that I had come to see him."

Prejean also finds inspiration in the example of Lloyd LeBlanc, the father of one of the teenagers slain by Sonnier and his brother Eddie. LeBlanc forgave the two brothers for the murder of his son.

"LeBlanc told me: 'If I hate them the way they hated David, then the hatred is going to kill me.' But he acknowledges that it's a struggle to overcome the feelings of bitterness and revenge that well up, especially as he remembers David's birthday year by year and loses him over and over again. Forgiveness is never going to be easy. Each day it must be prayed for and struggled for and won."

The lecture was presented by the Newman Centre, McGill's Chaplaincy Service and the Department of Culture and Values.