End of science? Nah

Science is so full of holes that two of the world's greatest theories clash, says Sir John Maddox.

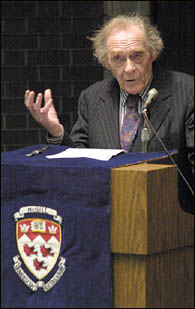

Sir John Maddox

Sir John MaddoxPHOTO: Owen Egan |

|

"We've come a long way in the last 500 years, but we're still ignorant of much more. That's why I say science is much nearer its beginning than its end," said Maddox, presenting "a checklist of our ignorance" to an appreciative crowd of some 600.

The theory of the big (Einstein's relativity, which tackles gravity) and of the very little (quantum mechanics), conflict, said the esteemed former editor-in-chief of Nature magazine in his Tuesday night lecture, titled "What Remains to be Discovered."

Maddox said scientists still don't know what space and time really are. Even the Big Bang theory about the creation of the universe - where there's no reputable cause suggested for the explosion - leaves Maddox scratching his head.

The brain has been mapped. "But can anyone say how the brain thinks? How the brain makes a decision? We don't know how cats decide to catch a mouse, or leave it alone."

The body's genetic building blocks are known, but no one knows how much in our behaviour is due to nature (inherited traits), and how much due to nurture (the things we are taught).

The message must have warmed the hearts of many long-time followers of the lecture series: A few years ago, science journalist John Horgan's controversial keynote address announced "The End of Science," leaving many incensed at the idea that there is nothing left to discover.

Science "has changed our lives for the better," said Maddox. "Science has made us healthier and wealthier and wiser." And research and the mass marketing of new technologies requires wealth. "Technology makes the case for economic growth... We need a more global division of labour, we need more globalization. I don't know whether the world is ready for that.

"There is probably some truth in the idea" that the "appallingly wide" gap between rich and poor countries helped lay the groundwork for September 11, Maddox added.

And so he had harsh words for naysayers who want to restrict science and learning. "Many believe we owe future generations something. It's ironical that people who hold that view also resist the idea that biotechnology should be used widely. It's the only important technology already in the cards that we have to hand over to future generations."

Maddox wants people to think about how long the human race should survive - he votes for "the rest of time."

That means using science to work out solutions to problems that are in the making. Like new diseases (or the return of deadly older ones, like influenza), monster asteroids (like the one that may have killed off the dinosaurs), and global warming.

Then there's the future of the human animal itself.

"We have indeed become so smart that we've opted out of natural selection," Maddox argued. Medical knowledge, for example, keeps alive many children whose undesirable genes might have died off in another time. "We are ill-prepared for the world in which we find ourselves."

Some researchers even say that the Y chromosome - the one that turns a collection of fetal cells into a male of the species - is on its way out. "Some say it is so small and so unstable that it won't last more than another 10 million years. I'm not saying there is a fatal flaw, I'm saying it's an issue worth keeping in mind as the centuries pass."

That could suggest a future focus on gene therapy or eugenics. "Many of the solutions are thoroughly illiberal," said Maddox. "That people should change their breeding habits... If that kind of dilemma arises [for the survival of the species], we should do everything we can to avoid illiberal solutions."

Maddox's talk was sponsored by the Beatty Memorial Lecture Series.